World's Most Dangerous Market: JGBs

Follow up article from video: Bank of Japan / Ministry of Finance Debt Monetization, Life Insurers, Asset Swaps, Foreigners' Curve Flatteners. Views on JGB policy, USDJPY 250+

JGB Supply vs Demand

Simply put - supply vs demand dynamics of the JGB markets put them on a path of ever-higher yields, especially at the long-end if left as is. But Japan’s attempt to fix it in and of itself may be what seriously and permanently breaks Japan far beyond repair, causes financial and economic destruction that the rest of the world is not exempt from.

Japan’s JGB market dilemma at the current juncture is one of market functionality first, followed by government debt financing costs. While market functionality may sound relatively more benign than a major economy defaulting on its sovereign debt, the government bond market in a state of structurally impaired dysfunction is extremely harmful, and even more delicate of a matter. JGB market functionality may even be more wide scale, and certainly more immediate in global market consequences if there is any misstep in this double-edged market functioning sword.

Bank of Japan Policy

That is why the following metrics and conditions do not matter for Bank of Japan policy decisions meeting-to-meeting:

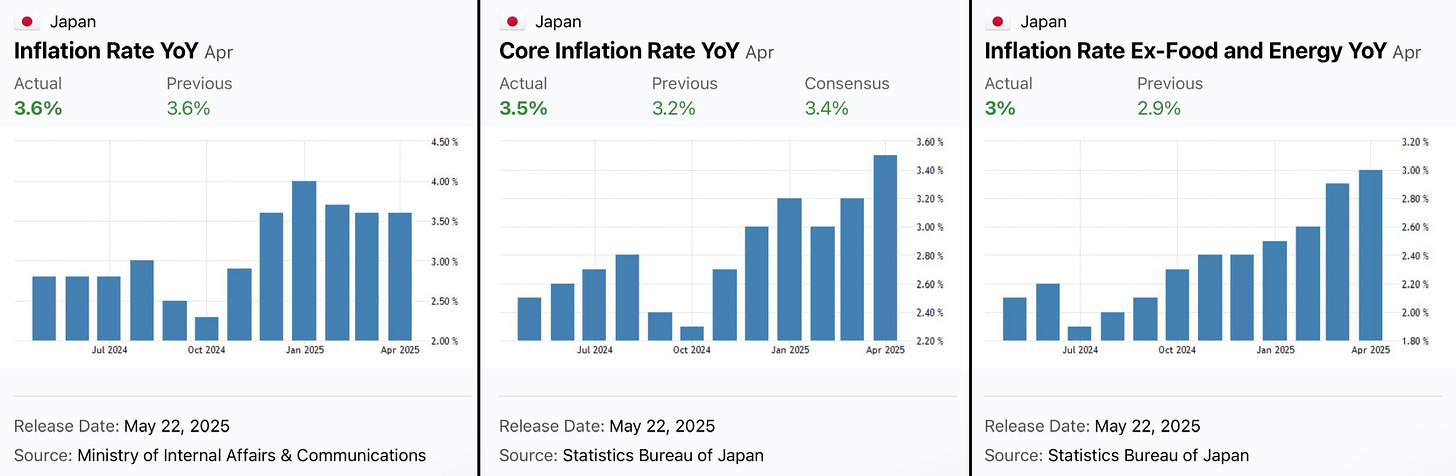

Japan Inflation

Currently, Japan headline CPI is not only higher than its major DM peers…

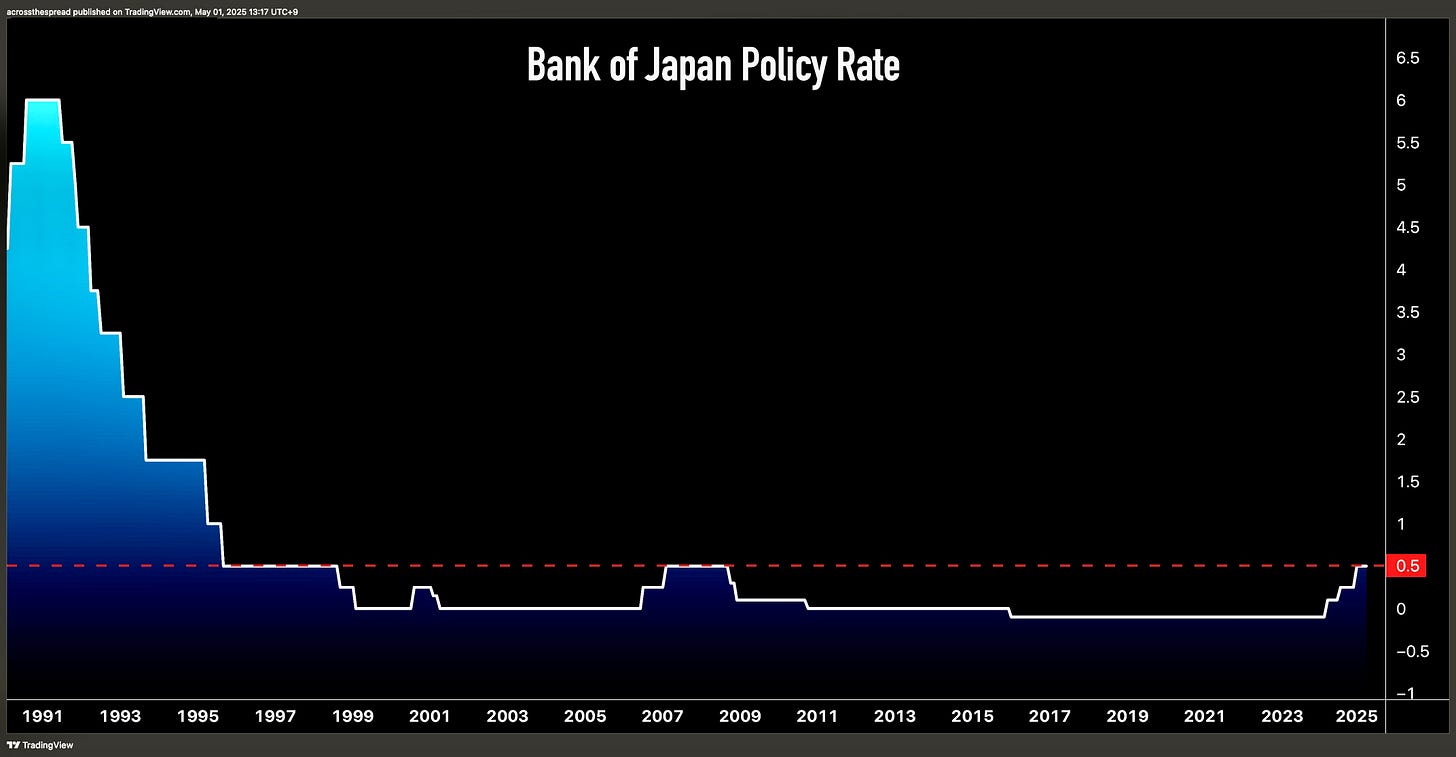

…but Japan core CPI has been above Bank of Japan’s “2% target” for three years running. What has BOJ’s policy “response” been over this above-target period of sustained inflation? Policy rates raised to 0.50% in 3 intervals over some 30 policy meetings with above-target CPI that had only started in March 2024, and tapering JGB purchases - but still very much actively purchasing JGBs.

What have their fellow major central bank peers done when faced with inflation? They also did the waiting game - but then ripped their respective policy rates higher by some +500 basis points (some out of starting in even deeper negative territory than BOJ was), and cut down their bond holdings - with some like the Bank of England actively selling their bond holdings into the markets. Again, BOJ’s front end policy rate is currently at a half percent above zero, and they are still very much actively buying JGBs - not not-buying, but buying, just less buying than before.

For those who say that this makes no sense, why isn’t BOJ tightening policy faster etc - the answer is very simple and very evident in everything I just showed and mentioned. Japan’s inflation has nothing to do with Bank of Japan monetary policy, and Bank of Japan monetary policy has nothing to do with Japan’s inflation. Meaning, Bank of Japan’s extreme levels of easing that was sustained over the course of a decade did not result in inflation for Japan, Japan’s inflation is the result of global inflation - the two are completely independent matters. So how or why would BOJ policy now have an impact on consumer prices? How does BOJ buying less JGBs or raising front-end rates for banks make the year-over-year change in the price of food in grocery stores to not rise? It makes perfect sense why BOJ isn’t seemingly “responding to inflation” - because there is no tie-in.

The only thing that inflation has to do with current Bank of Japan policy is that it provides for a (clearly nonsense) justification for their attempted “normalization” - or exiting of a failed experiment, without having to admit that normalization is underway due to acknowledgement and reversing of policy failure or necessity. If Japan consumer prices were to once again deflate, then BOJ would have no cover to justify their desperate attempt to unwind this permanent experiment.

Regarding what actually does matter to Bank of Japan decisions being made meeting to meeting, be it resulting in a change, or on-hold, here is what is most relevant for front-end rate policy, and long-end JGB buying/tapering policies respectively.

For BOJ interest rate policy (rate hikes):

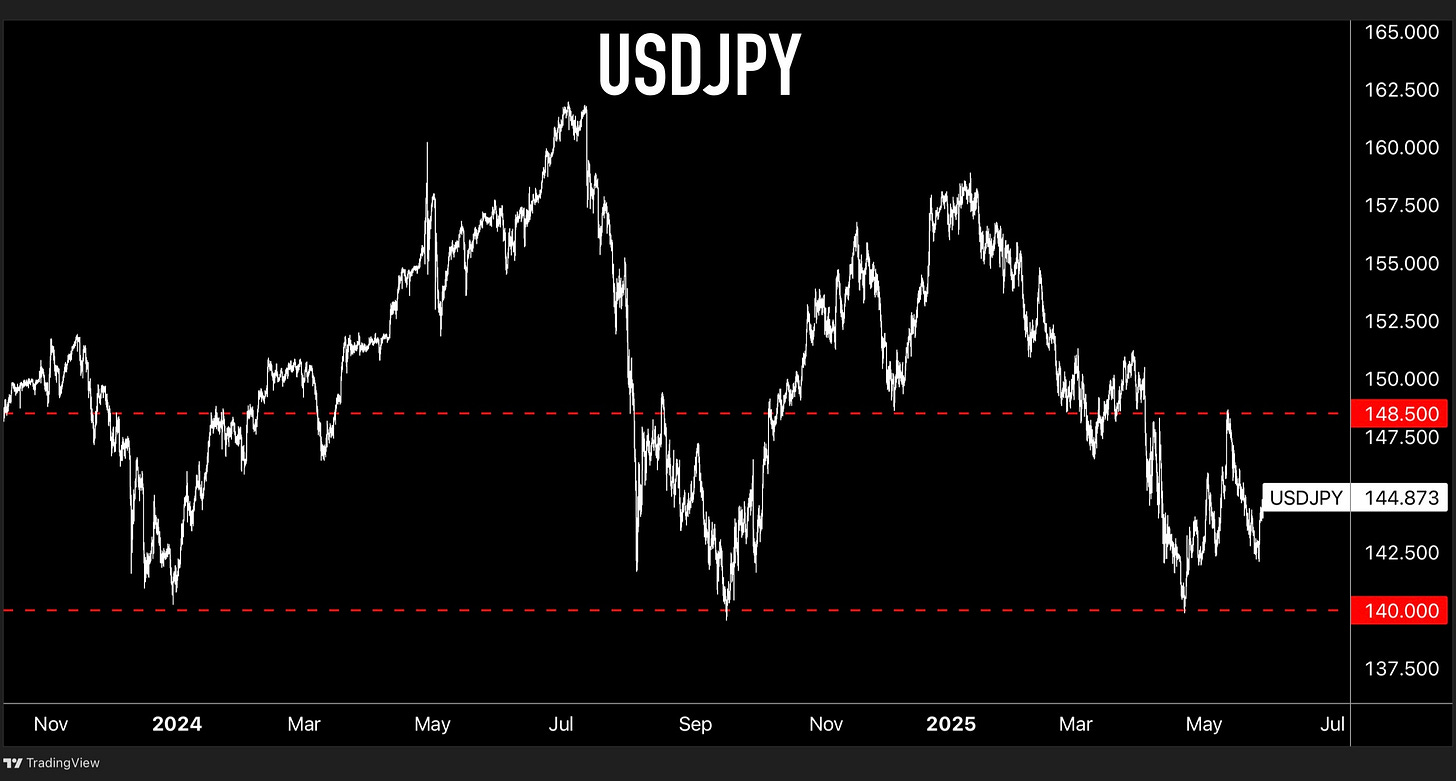

The yen

The “50bps ceiling” perception

The latter of the two being the more pressing issue than the former.

For JGB purchasing / tapering:

Long-end JGB yield levels and the velocity of increase

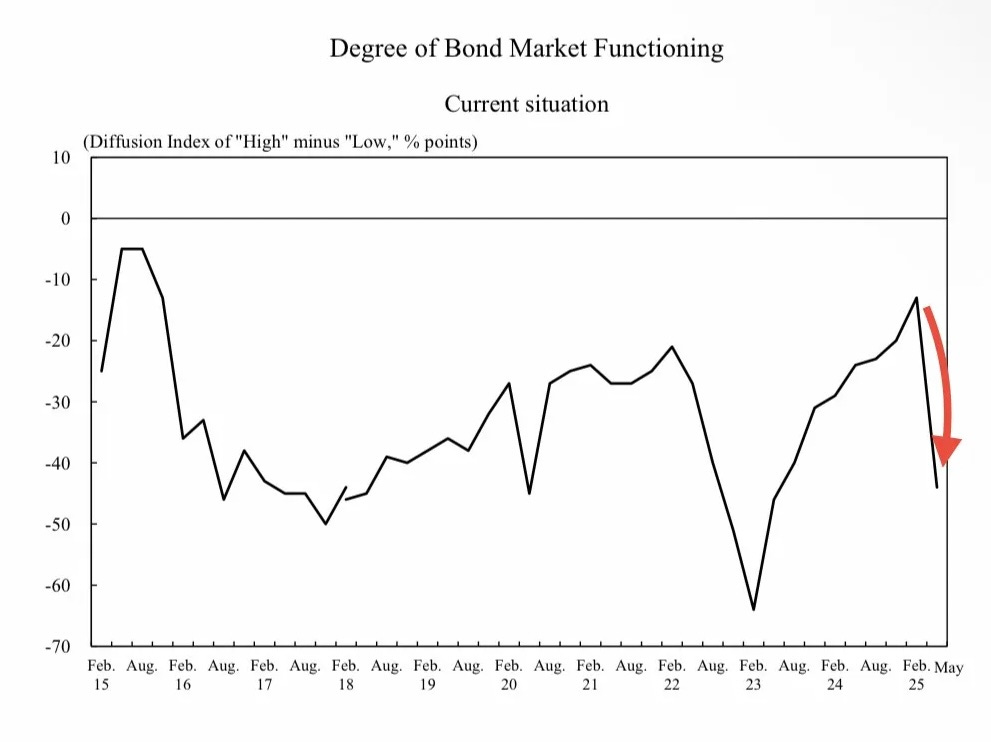

Bond market functioning

Which had been on a steady recovery, until sharply falling back towards deterioration in this latest reading from May.

These first two measures ultimately contribute to the big picture matter of…

JGB outstanding supply vs demand

Which is why BOJ board member Noguchi gave a speech and press conference in May amidst the spike in JGB yields, holding two separate (but non-conflicting) thoughts at once:

No rate hikes:

"When the outlook is so uncertain, there's no point acting on interest rates," he told a news conference, stressing the need to put off raising rates for the time being. "It's important to avoid moving and scrutinize developments."

No need to slow down JGB tapering:

“Yields on 10-year JGBs surged to nearly 1.6 percent in March 2025, but I personally believe that this rise -- albeit rapid -- cannot be regarded as disruptive, as it seems to have mainly reflected expectations among market participants of a higher terminal policy rate, given Japan's higher-than-expected economic growth and upswings in prices.

At the June 2025 MPM, the Bank will conduct an interim assessment of the plan for the reduction of its purchase amount of JGBs decided in July 2024, and announce a new guideline for its purchases from April 2026. In my view, it is unnecessary at this point to make any major changes to the current plan.”

So, regarding BOJ rate hikes going forward - they’re not coming anytime soon, if at all. The “50 bps ceiling” perception will remain a reality, until it isn’t. And barring a sudden, sharp and sustained episode of JPY crushing (and a time machine back to pre-Liberation days), remain a 50bp reality it will remain. Markets and surveyed economists have largely pushed back “the next hike” into 2026.

And thank heavens that half of the dual policy management is off the table - because the other half - the matter of long-dated yields, requires incredibly careful and focused orchestration by itself, and doesn’t need an additional policy lever in need of simultaneous maintenance.

How did the JGB market get here?

Debt Monetization

JGBs Outstanding

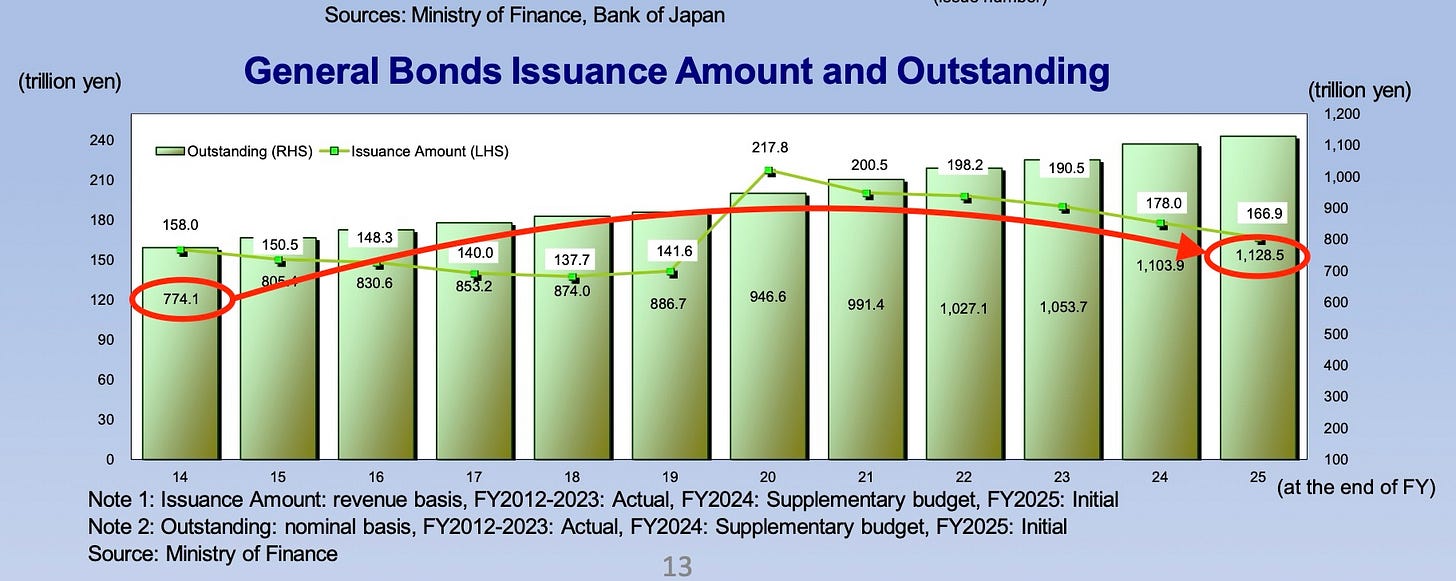

As of March 2025, the latest data available from Ministry of Finance shows Japan has ¥1.128 quadrillion (¥1,238 trillion, or more than $8 trillion) worth of JGBs outstanding. Note that this is just coupon bearing JGBs outstanding, and not the total amount of public debt outstanding - which is ¥1.324 quadrillion.

If you compare this insane figure to the amount of JGBs outstanding in 2014 (one year into Kurodanomics massive JGB buying / QQE-ing) at ¥774 trillion, Japan’s amount of JGBs outstanding had increased by more than +¥350 trillion (+45%) over the course of the decade.

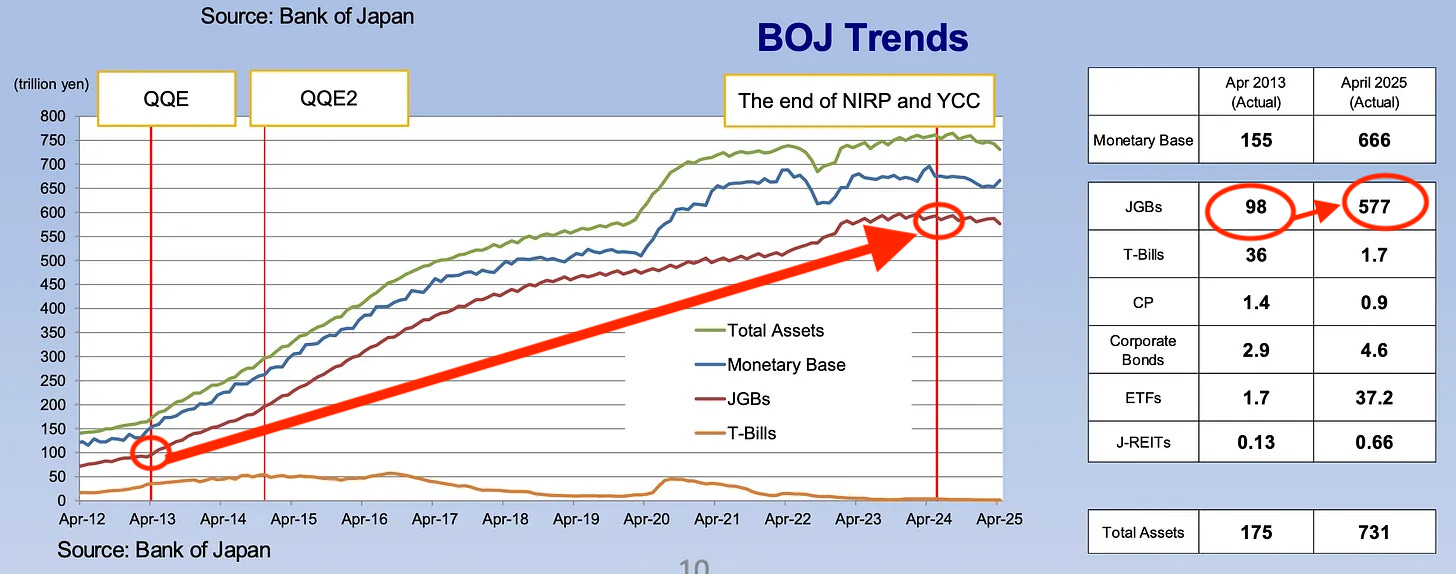

As of April 2025, the Bank of Japan holds ¥577 trillion worth of JGBs, or roughly half of all JGBs outstanding on its balance sheet. If you compare that figure to the ¥98 trillion worth of JGBs it had owned in April 2013, at the very start of BOJ embarking on this decade long (and still running) JGB mass binging experiment, that’s a +¥480 trillion increase (+488%) in JGBs owned by BOJ.

Put it all together into one picture depicting the state of Japan’s government financing over the past decade:

Ministry of Finance increased the amount of outstanding JGBs by ¥350 trillion, and the Bank of Japan’s ownership of outstanding JGBs increased by +¥480 trillion.

Which means that although the government had issued an insane amount of JGBs this past decade, on balance, the Bank of Japan acquired roughly ¥130 trillion more in debt than the government had borrowed “in the markets.” This is how Bank of Japan went from owning about 7% of JGBs outstanding in 2013 to more than half of JGB supply - again, supply that had also dramatically grown during this period.

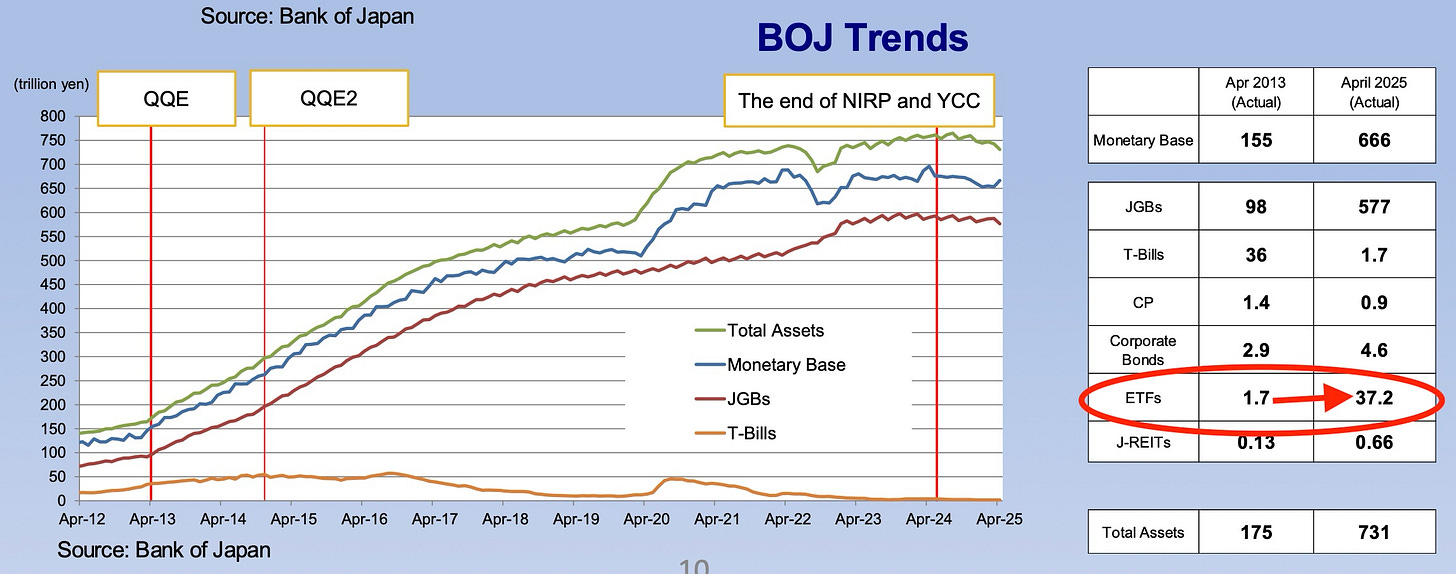

By the way - regarding the +¥35.5 trillion increase in equity ETF amount from from ¥1.7 trillion to ¥37 trillion over this period (20x gain)…

…yes, this is due to Bank of Japan having bought up a ridiculous amount of equity ETFs over the years - but that growth figure also reflects on-paper gains made from rising Japanese stock prices as well. BOJ had done most of its equity ETF buying in the first half of Kurodanomics, and largely stopped in recent years - prior to TOPIX and NKY225 indices having basically doubled in value subsequently.

I mention this, because its the exact opposite for the value of its JGB holdings - as JGB yields across the entire curve now far higher than they were when this half-quadrillion yen worth of JGB buying was taking place, the face value of all of those bonds had only decreased since BOJ bought them (much of which was bought with a negative yield). So the fact that Bank of Japan’s JGB portfolio size had grown so much while the value of those JGBs have been getting absolutely destroyed shows that the true scale of JGB buying is actually even more insane than just the figures above.

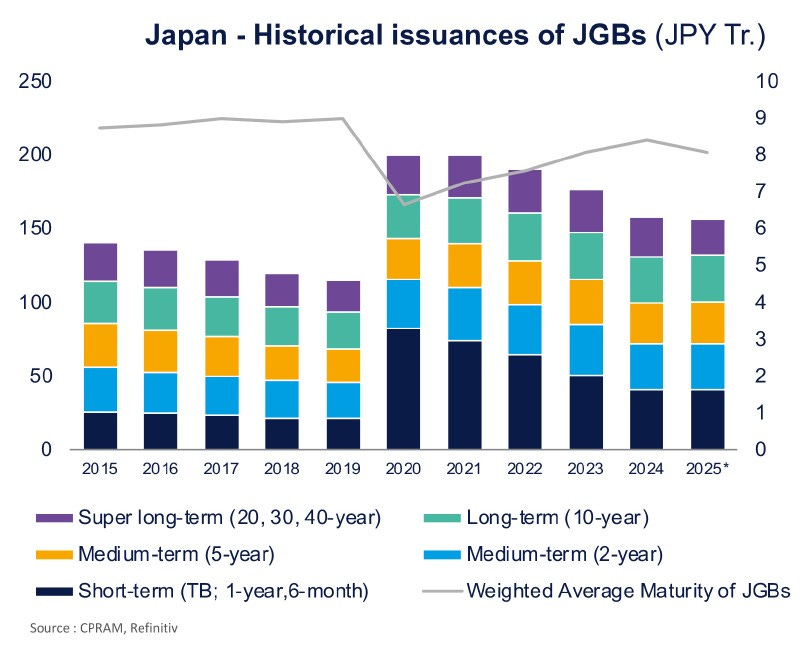

JGB Duration

If we look further, we’ll see that the average duration of JGBs outstanding has lengthened to nearly 10 years - as the Ministry of Finance’s issuance was very heavy at the super-long end of the curve relative to shorter maturities.

Long-dated JGBs (10Y ~ 40Y maturities) comprised of about 28% of the total JGBs outstanding across the entire yield curve in 2015. As of March 2025, JGBs with a maturity of 10 years or longer now comprise ⅓ of outstanding JGBs.

This increase in average duration of JGBs outstanding is the result of MOF both issuing more at the longer end, and keeping shorter-dated (10Y and under) issuance more or less stable as a percentage of the overall outstanding debt. The super-long end of 20-year and greater maturity JGBs outstanding has doubled in size to ¥150 trillion, and when combined with JGBs of 10-year maturities and higher, long-dated JGBs make up ¾ of the increase in the total amount of JGBs outstanding over the period.

And on the central bank side - in 2013, Bank of Japan’s JGB holdings had an average duration of roughly 4 ~ 5 years in remaining maturity. Today, Bank of Japan’s average duration has increased to approximately 7 years, as they had also bought up a ton of long-dated JGBs over the decade.

Has Bank of Japan been buying up long-dated JGBs because they exist in markets? Or do they exist in markets (are they being issued by MOF) because the Bank of Japan has been buying them?

The answer is the latter - of course. Perhaps in the first few innings of QQE on steroids, BOJ was buying what had already existed out there, and did so because it had already existed out there. But Abenomics kicked off more than a decade ago in April 2013, and only now in 2025 is the Ministry of Finance beginning to signal a larger than expected potential alteration of its issuance agenda.

The charts and data above of MOF’s JGB issuance vs BOJ’s JGB buying activity show what is very openly obvious and clear, even without the charts - that MOF’s ability to run up the debt pile as much as it did, and at as low an interest rate cost as it did over those years was only made possible because of BOJ.

See this chart from Michael Howell

of what MOF would have had to pay in borrowing costs if not for BOJ over the past decade:Mind you that even with BOJ artificially holding yields down, ¼ of Japan’s national budget currently goes towards servicing debt. Imagine if yields were north of 1% the whole time.

Bank of Japan’s unconditional buying and funding of the government has enabled said government to therefore continue to borrow and spend without limitations. If it were any other major developed nation that had a 250% debt to GDP ratio, economic laws of gravity would not even make such a figure possible to exist - because government and central bank would either cap and reverse it well before the 200% handle, or said country would have blown up on its way to 200%. 250% debt to GDP doesn’t make sense as an existing and sustained figure - not even for the mighty USA, unless you are specifically modern day Japan.

This is why I am saying that current long-end yield moves higher are not reflecting a Japan default - despite that being the overwhelming chatter here on the ground. If there truly were to be actual default risk priced into markets - how would 40Y JGB (or ANY) yields be in low single digit %, let alone sub-UST yields? Default means you aren’t going to get your coupon, or your principal paid back in full and on time. That means far higher yields than low-single digits to compensate investors for the risk of not getting your money back, or getting your money back in severely devalued yen while forgoing opportunities elsewhere if held to maturity, or risk of a major loss in principal if sold at higher yielding market conditions at any point in the next few decades. 30 and 40 year JGBs yielding 3%, though at record highs, is not a market reflection of any of that.

Japan can always pay back JPY-denominated debt, just as it has, and just as it will continue to, even if said JPY is worthless paper in and of itself.

And if Japan were to ever default on its debt, it would be by choice (for whatever horrendous reason that choice was made). That isn’t a default in the sense of a true sovereign default - inability to cover some amount of liabilities that outgrew a finite supply of funds which deplete faster than it could replenish.

So, current JGB markets yielding record highs at the 30Y and 40Y tenors are reflecting a severe supply and demand imbalance dynamic. When the central bank has bought up half of the debt outstanding, and has bought more notional in debt than the massively growing debt pile outstanding, then what the hell do you think happens with an attempt to “QT?”

In other words - when one entity not only becomes the largest active buying market participant AND majority holder of outstanding supply, and then attempts to step away, or rather, continue stepping forward, but just more slowly than it had been running at full speed for more than a decade straight - who or what entity can smoothly step in and fill that void?

Obviously, no one can, even if they wanted to - and nobody wants to take BOJ’s non-economic baton.

That said, BOJ was not the sole buyer of long-dated JGBs over the years. Of course they were the primary whales, but not the only ones. When long-end JGB yields skyrocketed by +20bps in a single trading day upon results of the worst 20Y JGB auction in decades was revealed - that market move is not a product of the BOJ buying less than they had previously been doing - somebody had to actually sell JGBs into the market to move prices down and yields up - and it certainly isn’t Bank of Japan actively selling long-end (or any) of their JGB holdings into the secondary cash market. Which means somebody had to own them to dump them. And yes, while it is technically possible to short-sell JGBs, this isn’t what is blasting the JGB long-end - as BOJ’s ownership of cash JGBs is at such extreme levels that in many cases, more than 50%, 80%, or even the entire 100% of a particular JGB issue is held by BOJ, making it very difficult and/or expensive for traders to locate, borrow and short sell cash JGBs in the market. JGB short sellers (foreign hedge funds engaged in the infamous widow-maker trade) get their downside directional exposure using 10Y JGB futures, and furthermore I would think and hope for their sake that they wouldn’t execute their opening of a new short position by just blasting the market to new record levels against themselves in such a haphazard manner - rather, that’s what a scramble for exits position unwind looks like.

This is long-selling, liquidating. So, who is (or was) long long-dated JGBs, why, and why are they selling their longs now?

The answer to this is what is critical to know, because these are the actual forces that are behind the surge in JGB and thereby UST yields.

There are a confluence of private sector forces at play that are pushing long-end JGB yields up to and through all time record highs against a backdrop of BOJ tapering and MOF issuing that is widening the supply vs demand profile - with three in particular:

One is the absence of buying from the Japan life insurance sector, which removes a critically reliable bid of support. But again, much like BOJ, this is the absence of buying.

The outright selling flows that actually moved markets are coming from two sources of position exiting - the asset swap unwind by domestic holders, and the curve flattener unwinding by yes, foreign investors, who have recently become a presence in long dated JGBs.

Let’s go through each one.

Japan Life Insurers

Japan’s domestic life insurance sector is a major global market impacting force that even casually astute investors keep tabs on what they are up to. The industry is dominated by 9 major firms with about $2.5 - $3 trillion USD worth of portfolio assets. They are whales in DM markets globally.

And in recent years, the Japan life insurance sector had also been a reliable buyer of long-end JGBs, and in such size that they (alongside BOJ) had kept a lid on long-dated JGB yield upside.

Japan lifers that had been loading up on long-end JGBs was due to two main reasons.

First is - because the BOJ was also buying, of course, and doing so with a very explicit, defined line-in-the-sand floor on prices guaranteed via Yield Curve Control. There was no need to wonder and guess if, or where, there was a central bank put - there was just a very clear central bank put. So of course the removal of said central bank put not only curtails buying demand, but there is an entire decade of JGB buying processes and habits that no longer have any clue what a “good price level” is, or just how to generally behave in actual green and red blinking ticker markets.

Second reason Japan lifers were predominant buyers of long-dated JGBs is because of regulation that was enacted this year - in which insurance companies’ balance sheets had to further minimize asset-liability mismatches. This had essentially forced insurance companies with long-dated liabilities to buy up long-dated assets as a matter of regulation, and not one of market choice. But now, Japan lifers have by and large fulfilled these regulatory obligations and therefore have stopped buying long-dated JGBs. Additionally, there is a structural decrease in demand for long-end JGBs from Japan lifers because of Japan’s aging demographic picture - less customers of life insurance means less need to match liabilities vs assets.

Recall a year or two back - this whole narrative of “…if/as JGB yields rise, Japan investors will repatriate their massive foreign holdings back home because domestic bonds now offer a yield?” And I had always said that this idea of dumping trillions in foreign bond holdings to plow into JGBs because yields are rising was NOT how it would go down - because if BOJ truly was on the start of a “rate hiking cycle,” then why in the hell would they jump into JGBs the moment yields rise? They would very likely wait until BOJ was done crushing the JGB market before any serious capital reallocation - and even if they signal intent to increase JGB allocations upon fiscal year earnings projections and presentations, they will hesitate to buy if and when JGB yields move rapidly higher - rather than blindly dive in.

Well, it seems that is the case.

Fukoku Mutual said they will buy into surging yields on long-dated JGBs in March - until it was time to actually pull the trigger.

Bloomberg: Major Japan Life Insurer to Pile Into Domestic Super-Long Bonds

Fukoku Mutual Life Insurance Co. plans to invest in Japan’s super-long government bonds this fiscal year after their yields skyrocketed, and is considering shifting from foreign debt.

“Yields have risen to levels that align with our investment perspective, so we will proceed with bond re-balancing while actively increasing holdings,” said Junya Morizane, general manager of the insurer’s Investment Planning Department. “There is ample room to continue purchasing super-long bonds.”

“It has been a tiring couple of weeks,” said Morizane. “We decided on this plan in March, but the underlying assumptions have changed significantly.”

“There’s been so many meetings and we are analyzing how far our revenue will fall and how much we can recover in this environment,” he said.

What’s the problem, Fukoku Mutual? Long-end JGB yields are doing what you said was attractive to buy - why not execute as planned and stated?

Because when push comes to shove, it’s extremely difficult to actually try and catch a falling knife - particularly for the one asset that has never fallen, nor been a knife for which to catch.

Long-end JGB investors don’t know that they don’t know how to invest in long-end JGBs post-Kurodanomics. And those who do know that they don’t know are not buying JGBs for that very reason.

NIKKEI: Japan life insurers set to cut JGB holdings by $9bn

TOKYO -- Japan's top life insurance companies plan to reduce their holdings of Japanese government bonds by 1.3 trillion yen ($9.1 billion) overall in fiscal 2025, in a shift from their response to new capital rules.

Nippon Life Insurance will do so for the first time since fiscal 2016. Nippon Life replaced around 2 trillion yen worth of lower-yield government bonds in fiscal 2024, with more planned for fiscal 2025. Akira Tsuzuki, executive officer and head of financial planning, said at a press conference on Thursday the amount in fiscal 2025 might exceed that of the previous year.

Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance reduced its domestic bond holdings, including JGBs and corporate bonds, by 390 billion yen in fiscal 2024 and plans to make a similar reduction in fiscal 2025.

Daido Life Insurance plans to increase its domestic bond holdings, focusing on ultralong-term bonds. "The duration of our liabilities is long at 24 years, so there is room to extend the maturity of assets by buying 30- and 40-year bonds," said the head of the company's investment planning department. Daido increased its domestic bond holdings by over 300 billion yen in fiscal 2024 and plans to increase by around the same amount in fiscal 2025.

Fukoku Life Insurance had held back from buying JGBs over the risk of greater unrealized losses due future interest rate increases. But the company intends to increase its holdings in fiscal 2025. "Government bond yields have risen to a level that is appropriate for investment," said Junya Morizane, head of the investment planning department.

Dai-ichi Life Insurance plans to keep allocating capital to private equity and real assets such as property and infrastructure. Hedge funds and private debt will be areas of focus this fiscal year.

The one interesting standout to me was Japan Post - which has an absolutely massive portfolio size. Here is what their plans are, according to this same Nikkei article:

Japan Post Insurance plans to buy up to 1 trillion yen of domestic bonds, but due to a large number of redemptions, its holdings are expected to decrease as they did in fiscal 2024. Japan Post Insurance may shift from hedged foreign bonds to yen bonds depending on interest rate trends.

The reason this is interesting is because Japan Post is essentially a semi-privatized, former government institution until going public in the last decade. But they really aren’t a “private sector” institution - as Ministry of Finance remains their top shareholder by law (government has to own a minimum ⅓ stake)

Japan Post Holdings CEO is Hiroya Masuda - here’s his resume:

Masuda (and others like him) are an agent of government first, and a shareholder minded publicly listed company CEO second.

If I had to guess, Japan Post and GPIF may end up being the JGB long-end buyers of last resort - whether they like it or not.

Asset Swap

An asset swap is a structure that JGB investors (mostly domestic long-onlys) trade, which gives them a synthetic floating-rate long-term JGB for the purposes of hedging against rising yields - as floating rate cash JGBs don’t exist (note that MOF is trying to roll out short-dated floating rate JGBs within the next year).

Investor buys a 30Y cash JGB, for which they receive a fixed rate of income stream. They then face a counterparty (domestic megabank) and trade a JPY 30Y Interest Rate Swap (IRS) OTC - which they exchange (pay) their fixed rate and receive what is essentially a floating rate (overnight rate + spread) while still holding their 30Y cash JGB.

The 30Y JGB yield and 30Y JPY swap rates should more or less be close to each other, as the IRS is a derivative of the cash JGB - and they did indeed move closely aligned - until 2024, when they started to diverge, with the spread getting as wide as 60bps.

This non-economic divergence is yet another symptom of JGB market’s conditions of poor functioning - as a healthy, liquid and robust market would have arbs close up the spread.

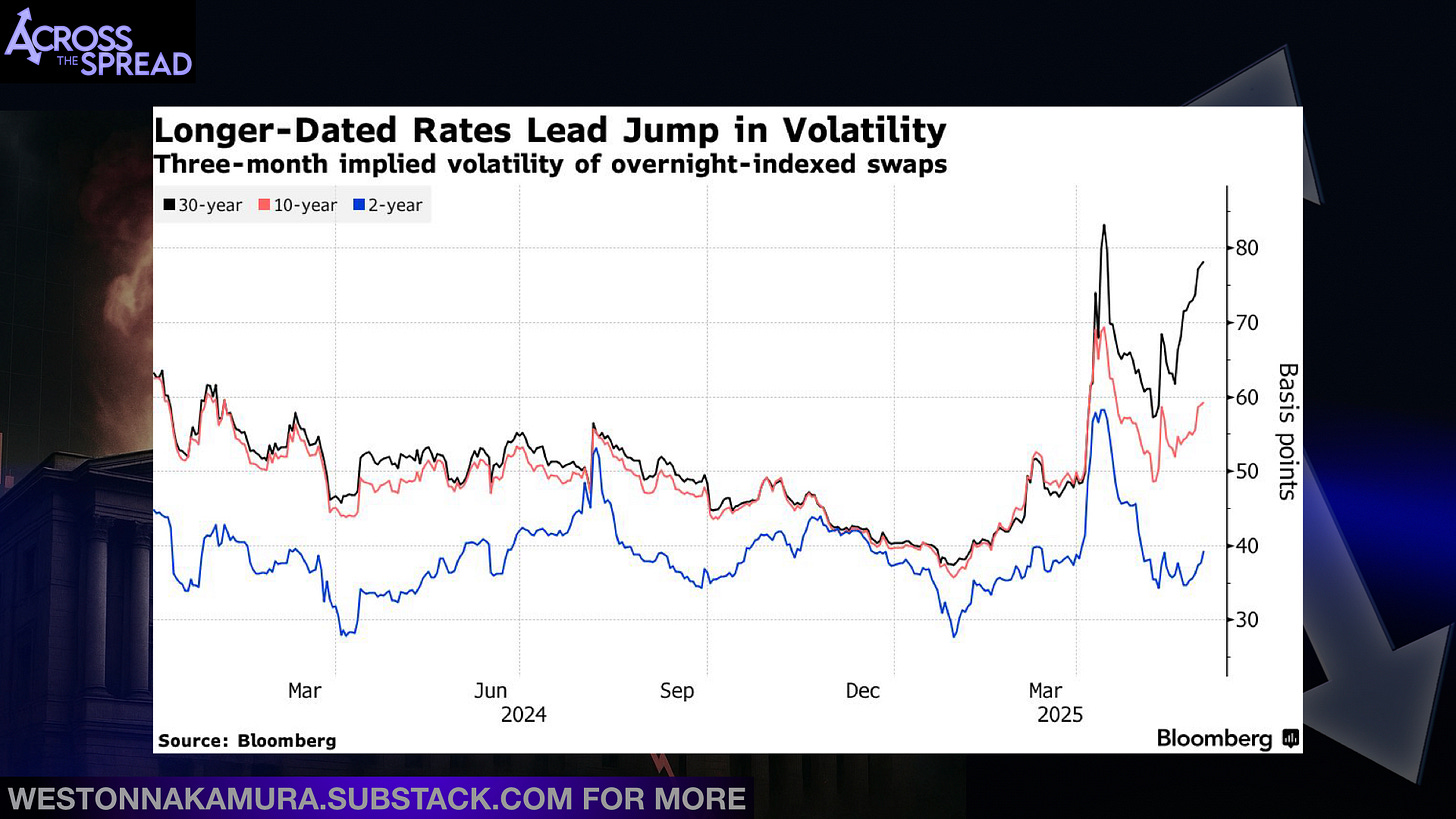

Then in April-May 2025, amidst the sharp long-end rate volatility…

…these asset swap trades were force-liquidated, and JGB 30Y swap spreads blew out to nearly a full 1% wide from May 20th (horrible 20Y JGB auction day).

What’s alarming isn’t so much that these spreads had blown out - rather, it’s that this dislocation wasn’t immediately reversed, and instead remained extremely wide near ~90bps for days on end. To put the asset swap trade on under these conditions would normally be a no-brainer, as you’re essentially picking up a “bonus” ~90bps. But nobody did. Where are the arbs to close up this gap? Where are the synthetic floating-rate exposure seekers?

Nobody wanted to, or was able to touch JGB 30Ys - they were (forced) sellers, or sidelined. Or both.

The asset swap unwind was one of the two primary forces that spiked long-end JGB yields during this period - and again, these are by and large domestic Japanese.

The other long-end JGB sell force in markets were foreigners - and not short selling foreigners, but long-liquidations.

Foreigners’ Curve Flattener

We all know the widow-maker trade - foreigners who short JGBs and get steamrolled by BOJ - a trade that has gone on for decades.

Well, in 2025, foreigners started buying long-dated JGBs in record size - and in May, they got reverse-widowmaker’d.

Foreigners weren’t going outright long long-dates JGBs - they were putting on a JGB 10s30s curve flattener trade: short 10Y JGBs / long 30Y JGBs, betting that the JGB curve would bear-flatten as the BOJ would continue to hike rates after doing so in January.

Note that while yield curve flatteners / steepener trades are typically done on the front end and back end of UST and other yield curves (2s10s, 2s30s etc) - the 10Y is “front-end” leg of the JGB curve, because: 1) 10Y JGB yields are still extremely suppressed due to remnants of YCC that had specially pinned down the 10Y tenor, and 2) 10Y is where the only liquid JGB futures exist, should the trade involve shorting the 10Y leg (which in this case, it did). Meanwhile there is little opportunity to put on any such trade on USTs.

So, if it is believed that BOJ was “normalizing” - then the unusually steep JGB curve would flatten out and head towards where other DM yield curve peers were.

As such, not only did foreigners buy a record amount of long-dated JGBs in early 2025, but that buying flow ended up being a major downward force on long-end JGB yields - enough to offset domestic life insurers.

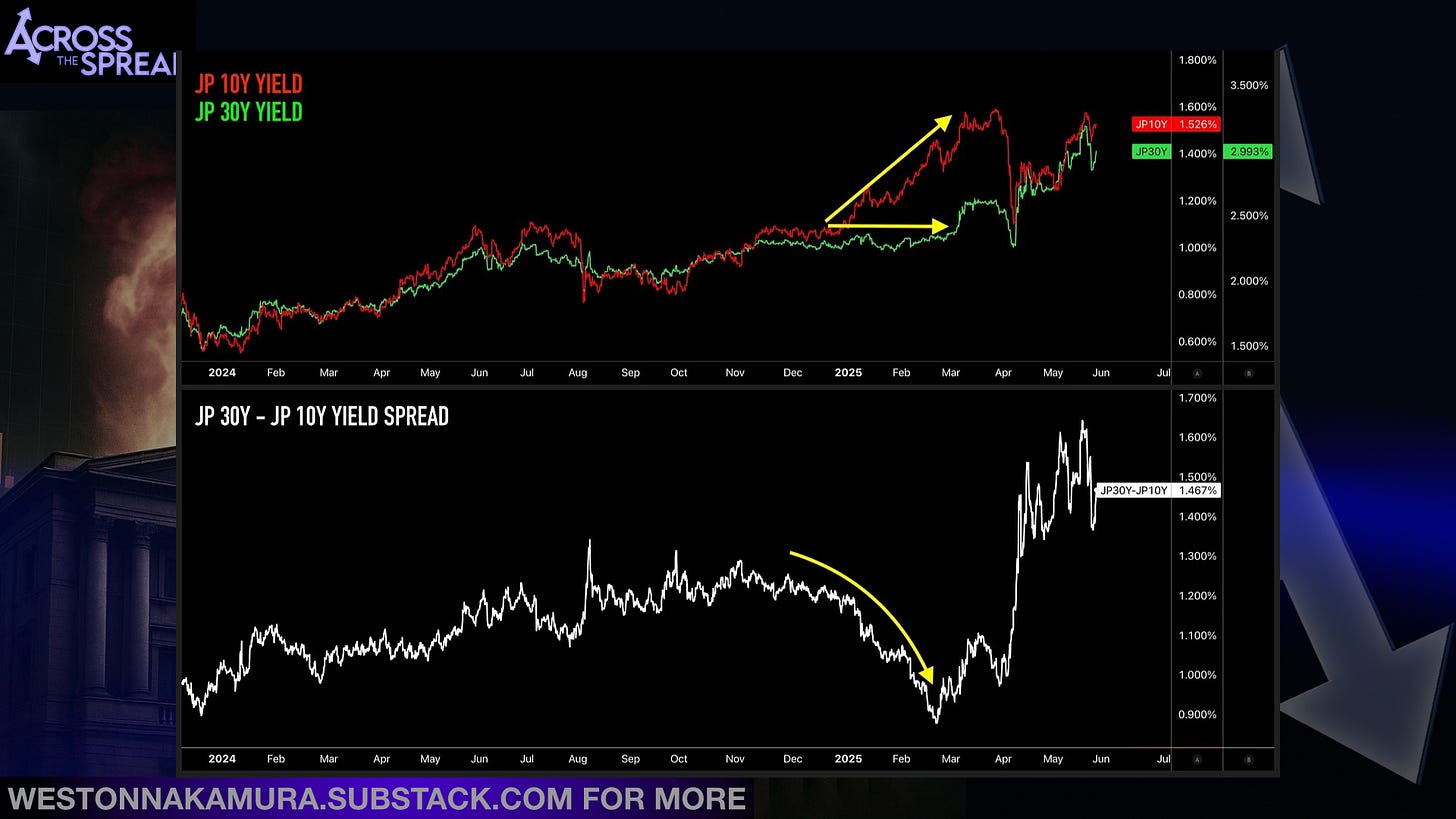

You can actually see this short 10Y JGBs / long 30Y JGBs trade getting piled into very clearly in charts - as 10Y JGB yields began to surge while 30Y JGBs remained flat in early 2025:

That divergence and curve flattening in the chart above is not foreigners getting the trade right (maybe the earliest of them) - that’s them putting that trade on.

Then in April, yields everywhere collapsed in the immediate aftermath of Liberation Day (which I mention in my video - why is it that nobody remembers / discusses this part of the yield move?) - and although JGB 30Y yields fell, 10Y JGB yields got absolutely crushed, losing ⅓ of its nominal yield in an instant, and subsequently blew apart the JGB 10s30s flattener trade into pieces as long-end JGB yields reversed and skyrocketed.

What you’re seeing in the bottom panel of the chart above is a long, wrenching, relentless period of this trade unwinding over the course of 2 months. This isn’t a quick death and recovery - this is traders holding on for dear life and maintaining, even averaging down, and eventually getting blown out over and over.

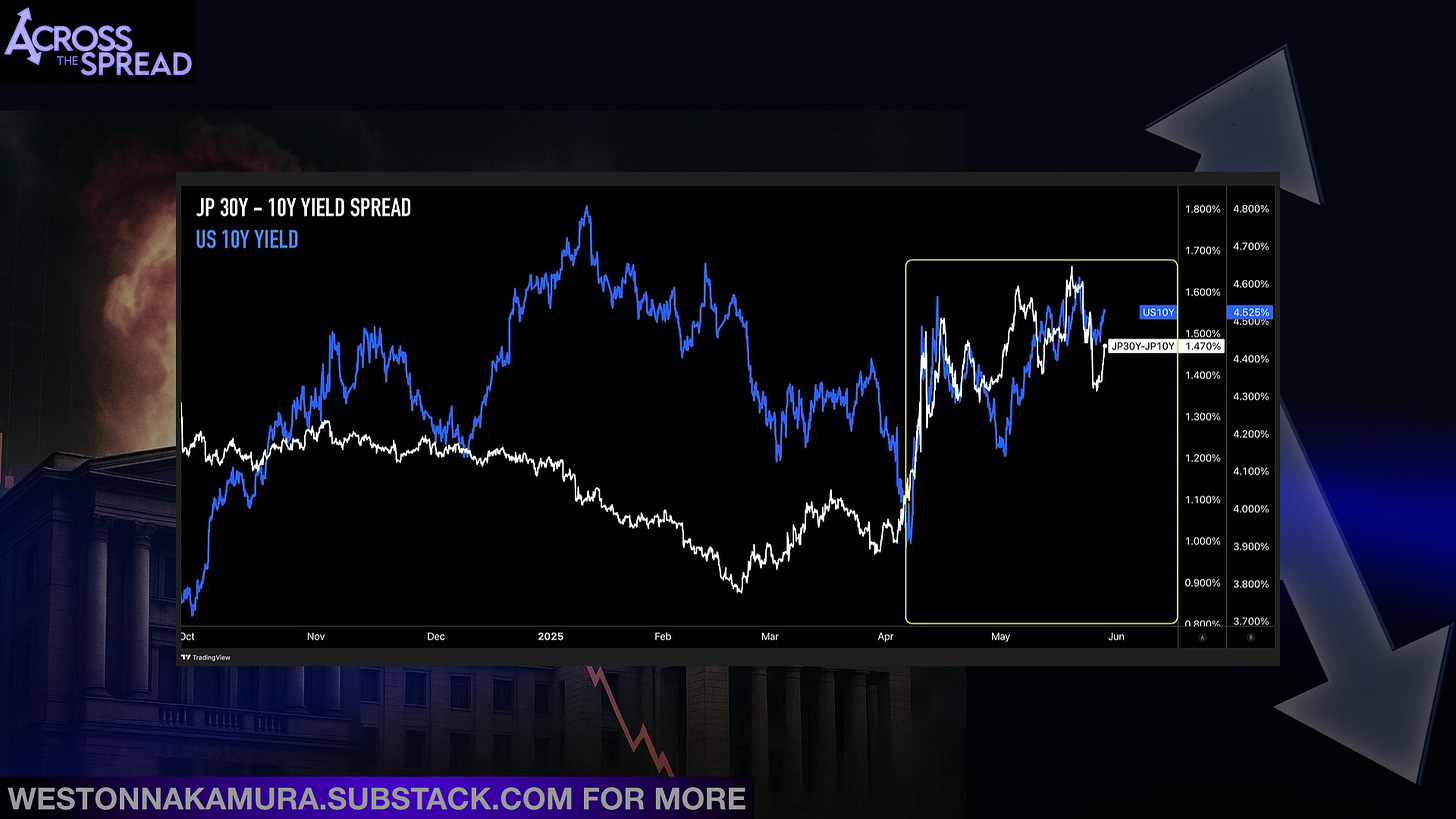

And this foreigner-led JGB yield curve flattener trade blow up had flooded out, dislocating and correlating markets.

This is why I keep saying that it is so incredibly stupid for such a broad consensus to just accept that some tectonic shift in generational flows into US markets had suddenly reversed in a brand new era of “sell America” underway - just from observing a window of literally 2-5 trading days. Even if that ends up being the case, the initial market moves were positioning unwinds that dislocate normal price action relationships and correlate strange bedfellows. In other words - these aren’t the conscious, purposeful and willing actions of investors on display, it’s PnL destruction.

So, those are the two primary reasons why long-dated UST yields via long-dated JGB yields had shot upwards. Not fucking Congress debating SALT within the bill.

But ultimately, it’s the Bank of Japan lifting its foot off the JGB buying pedal after pressing it on the floor for a decade straight. And it’s not just BOJ buying or lack thereof itself - it’s the market conditioning that had become entrenched. Private sector investors could net-buy JGBs and cap yields completely by themselves if they want to - but they would only do so if they know that BOJ is present in markets. If BOJ is somehow able to trick investors into thinking that they’re there to buy without actually buying, then perhaps JGB yields will stabilize by market forces alone - but such an illusion can only last for so long before yields move higher and investors wait to see if BOJ buying is actually there. And only when BOJ actually steps back into markets will the “assurance flows” resume. So pretending alone is not a lasting solution by any means.

Japan’s “Liz Truss Moment”

We all know of the infamous “Liz Truss Moment” - which I have been saying is a mis-labled event that should be referred to as the “UK LDI Moment” instead, as it was the UK pension system’s mechanical forced liquidations of leveraged long-dated UK gilts that had shot UK 30Y and 40Y yields up +100bps within a week and called for the Bank of England to step in and conduct emergency YCC by directly offering to buy long-dated UK gilts in unlimited size for the purposes of immediate-term market stabilization. Yes, the Truss/Kwartang mini-budget was the trigger catalyst to initiate the long-end UK gilt sell off, but the subsequent price-indiscriminate forced deleveraging was not some rapid and continuous fundamentally based repricing of UK long term borrowing costs being reflected in market behavior.

Nonetheless, the “Liz Truss Moment” had come to define a modern era of bond markets governing government deficits and debt levels - so, fine - for the purposes of using the terminology that refers to bond market investors’ influence over government policies which carry relevance to its debt and deficit levels, I will refer to that as "Liz Truss Moment.”

I mention in the video how PM Ishiba has seemingly no awareness, sensitivity for, or care over JGB yield levels and Japan government borrowing costs - as per his very casual "Japan is worse than Greece” comment made at a time when 30Y JGB yields had been on a steep rise and were bursting at the seams of breaking above 3.0% - which they did shortly thereafter.

And therefore, PM Ishiba himself doesn’t seem to have any “Liz Truss Moment” of discipline instilled within himself, whereas nearly everyone else around the world, including Trump, seems to show some level of mindfulness around bond market activity.

What is interesting in Japan’s case is that there actually is some iteration of a Japan “Liz Truss Moment” that is influencing, if not governing its debt issuance practices by its primary creditor / holder of JGBs: Bank of Japan.

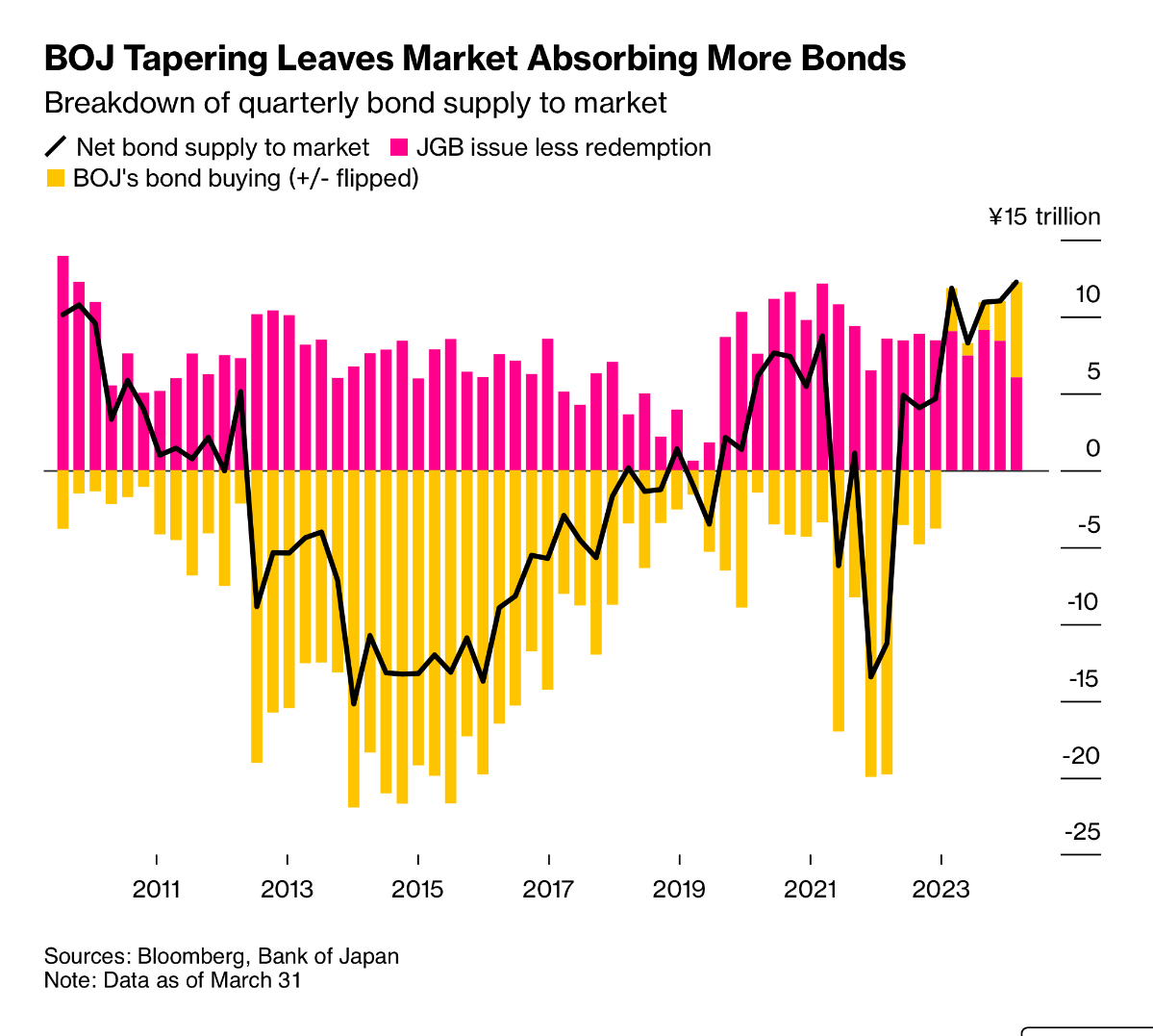

For more than a decade, BOJ and its enormous JGB buying policy had enabled, if not encouraged the Japanese government to keep issuing debt, particularly at the long-end. See this chart from Bloomberg, with net bond supply (black line) almost perfectly in-line with BOJ bond buying (inverse).

But now that BOJ is tapering and thereby flooding JGB supply into the markets, that is actually forcing the government to think about how to term its debt issuance. In other words, Japan’s largest creditor is instilling a Japan “Liz Truss Moment” onto the Ministry of Finance - its just that said largest creditor to the Japanese government is its own central bank.

USDJPY 250+

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Across The Spread to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.